A new, self-healing lithium-ion battery may improve the lifespan and safety of today's energy-storage technologies, researchers report.

A new, self-healing lithium-ion battery may improve the lifespan and safety of today's energy-storage technologies, researchers report.Rechargeable Li-ion batteries, like any batteries, tend to break down over time.

". . .many different types of degradation happen, and fixing this degradation could help us make longer-lasting batteries," said University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Materials Engineer Scott White, who reported the battery's details at the February 20 American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting.

One site of damage is the anode, a battery's negatively charged terminal. As a battery charges and discharges, the anode swells and shrinks. Over time, this cycling creates cracks that can interfere with the flow of current and, ultimately, kill the battery.

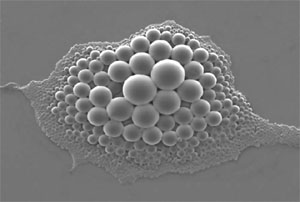

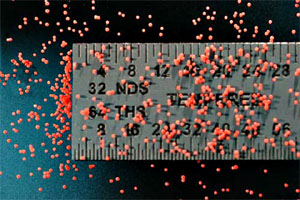

To counteract this, White embedded tiny microspheres inside the graphite of an anode. As cracks formed, they tore open the plastic shells, releasing the contents: Indium gallium arsenide. This liquid metal alloy seeped out of the spheres and filled the anode's cracks, restoring the flow of electricity.

Damage to a battery—or a short circuit between components—can cause problems other than a shorter lifespan. Out-of-control currents have been known to create hot spots that grow into a raging fire.

Damage to a battery—or a short circuit between components—can cause problems other than a shorter lifespan. Out-of-control currents have been known to create hot spots that grow into a raging fire."It's not a common occurrence but when it happens, the consequences are severe," White said. Battery fires have prompted laptop recalls by Dell and Hewlett-Packard, and the U.S. Department of Transportation has proposed stricter rules for cargo planes that transport large quantities of lithium-ion batteries.

To safeguard against this type of failure, White developed a second kind of microsphere made of solid polyethylene—an inexpensive and widely available plastic. A small quantity of these spheres embedded in the anode and other battery components can function as a safety cutoff switch.

"We've tested this in real batteries," said White, "and it works beautifully."